This Election Mom Knows Best Again

A Year of U.South. Public Opinion on the Coronavirus Pandemic

Well-nigh a year ago, state and local governments in the United States began urging residents to adjust their work, school and social lives in response to the spread of a novel coronavirus commencement identified in Prc.

Americans could hold on a few things at that early stage of the U.South. outbreak. With restaurants, stores and other public spaces around the country endmost their doors, most saw COVID-19 as a serious economic threat to the nation. Nigh approved of their state and local officials' initial responses to the outbreak. And they by and large had conviction in hospitals and medical centers to handle the needs of those stricken with the virus.

As the pandemic wore on, however, at that place was less and less common ground. Indeed, the biggest takeaway most U.Due south. public opinion in the starting time twelvemonth of the coronavirus outbreak may be the extent to which the decidedly nonpartisan virus met with an increasingly partisan response. Democrats and Republicans disagreed over everything from eating out in restaurants to reopening schools, fifty-fifty every bit the actual touch on of the pandemic fell along unlike fault lines, including race and ethnicity, income, age and family unit structure. America's partisan divide stood out fifty-fifty by international standards: No state was as politically divided over its regime's handling of the outbreak as the U.Due south. was in a 14-nation survey last summer.

Equally the COVID-nineteen outbreak in the U.Southward. extends into its 2nd year – with more than 500,000 dead and major challenges to the nation'southward economic system – Pew Research Center looks back at some of the key patterns in public attitudes and experiences nosotros observed in the first year of the crisis.

In early surveys, a sign of things to come

Our beginning COVID-19 survey went into the field on March 10, 2020. We interviewed near nine,000 Americans over the course of the next seven days – a menstruum that saw the World Health Organization declare the virus a pandemic; President Donald Trump declare a national emergency and ban travel to the U.S. from parts of Europe; and the White House advise Americans to avoid gatherings of more than x people.

News most the virus was breaking then quickly that public concern ticked up noticeably even within the weeklong field period of our survey. By mid-March, all fifty states had reported coronavirus cases. Past the terminate of the month, the U.S. had more than cases than any other country, and a bulk of Americans were nether some kind of stay-at-home order.

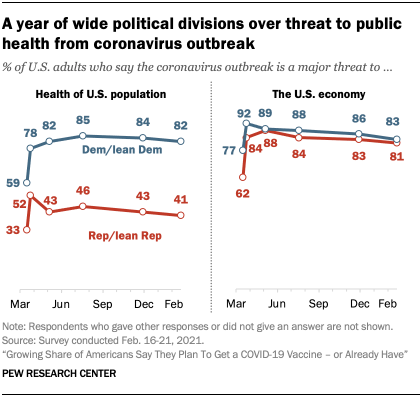

There were already some indications of the partisan divide over the virus in that offset sounding. While majorities in both parties anticipated the economical issues hurtling toward the nation, Democrats and Republicans differed sharply over whether the virus was a major threat to the health of the U.Southward. population. Near six-in-10 Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (59%) said it was, compared with only a third of Republicans and GOP-leaning independents.1 That 26 percent point gap would grow to around 40 points as spring turned to summer so fall.

Other divides also became apparent in that first survey. They included heightened health concerns amongst Black and Hispanic Americans, as well equally greater economical concerns amid workers with lower incomes and less formal schooling. Both would become recurring themes throughout the pandemic and the severe recession it brought on.

Overall, our first polling on COVID-19 showed that the public had mixed expectations about how the outbreak would play out in the months ahead. That wasn't necessarily a surprise, given that virtually Americans had little or no experience with a pandemic. In mid-March, only around a 3rd of U.S. adults (36%) expected the virus to pose a major threat to the mean solar day-to-day life of their community.

By late March and early April, the mood had clearly changed. 2-thirds of Americans – including majorities in both parties and beyond all major demographic groups – saw COVID-19 as a significant crisis at that time. Large majorities saw a recession or low coming, predicted the pandemic would last more than six months, said the worst was still to come and anticipated that there could be at least some disruptions to Americans' ability to vote in the presidential election in November. All of those things would turn out to be true.

A trust gap over primal sources of information

The inflow of a first-in-a-lifetime pandemic created a sudden demand for average people to discover and procedure big amounts of complicated and rapidly evolving information. Americans turned to many different sources for that information, but two commonly cited ones, the White Business firm and the news media, brought out particularly sharp partisan differences in attitudes.

In tardily March, views of how Trump was treatment the outbreak were already starkly dissever along party lines. Around eight-in-ten Republicans (83%) said the president was doing an excellent or good job, including 47% who said he was doing an fantabulous chore. A about identical share of Democrats (81%) rated his response as only off-white or poor, including 56% who said it was poor.

In early April, around two-thirds of Republicans (66%) said Trump was quick to take the major steps needed in response to international reports of the outbreak; 92% of Democrats said he was too tiresome off the marker. In the same survey, 69% of Republicans said Trump was accurately characterizing the severity of the COVID-nineteen situation; an even larger share of Democrats (77%) said he was making it seem better than it really was. Fall came but the partisan divide remained: In early September, around 8-in-x Republicans (79%) said the president was giving the country the right bulletin on the virus; a bigger proportion of Democrats (90%) said he was delivering the wrong message.

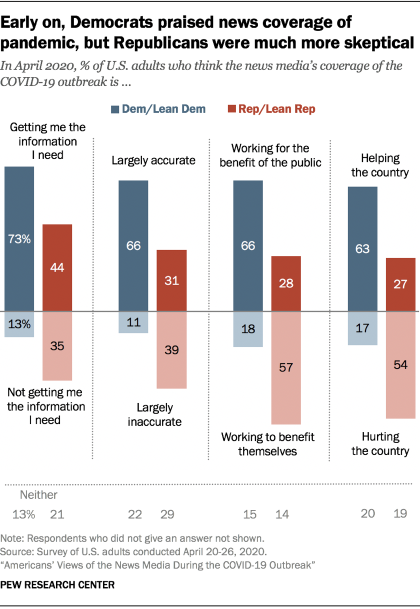

If views were partisan when it came to the president, they were only slightly less so when it came to the news media. In mid-March, 89% of all Americans said they were following news about the outbreak very or adequately closely. But Democrats were already much more likely than Republicans to say the media had covered the pandemic at least somewhat well (80% vs. 59%), while Republicans were more than likely than Democrats to say the media had exaggerated the risks of the outbreak (76% vs. 49%).

Every bit the pandemic continued, divisions over the media became more apparent. In late Apr, majorities of Democrats said the news coverage of the outbreak was getting them the data they needed (73%), was largely accurate (66%), worked for the do good of the public (66%) and helped the land (63%). Fewer than half of Republicans agreed with each statement.

Past September, around viii-in-ten Democrats (81%) continued to say the media were doing very or somewhat well covering the outbreak, but the proportion of Republicans who agreed had fallen beneath one-half (45%).

On many subjects related to the coronavirus, public attitudes differed not only past political political party, simply within each political party, depending on where people turned for news and information. Republicans who relied on Trump and the White House for COVID-19 news, for example, were consistently more probable than Republicans who turned elsewhere for news to rate Trump's response highly – and the media's response poorly.

Meanwhile, with the perceived trustworthiness of information from both the White House and the media deeply divided along partisan lines, Americans expressed concerns most the proliferation of misinformation.

As early on as mid-March, around half of Americans (48%) said they had seen at least some information about COVID-xix that seemed completely made up, on subjects ranging from the origin of the virus to its risks and potential cures. In early June, sizable shares in both parties – but peculiarly Republicans – said they were finding it harder to tell what was true and what was imitation about the outbreak. And conspiracy theories began to proceeds a foothold: In the same June survey, a quarter of U.S. adults saw at least some truth in the theory that powerful people had intentionally planned the outbreak. Republicans were well-nigh twice as likely as Democrats (34% vs. 18%) to say the claim was probably or definitely true.

Divisions over shutdowns, social distancing and masks

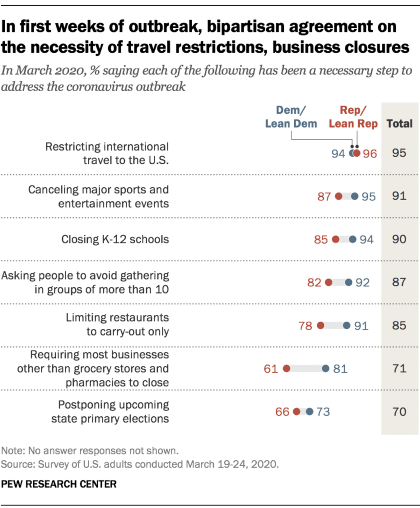

Information technology may seem difficult to believe today, but in late March 2020, there was strong bipartisan support for a variety of government-imposed shutdown measures. At the time, wide majorities in both parties supported restricting international travel to the U.S., canceling sports and amusement events, closing 1000-12 schools, request people to avoid gatherings of more than 10 people and halting indoor dining at restaurants.

The restrictions didn't always wear well over fourth dimension, peculiarly as governors and other leaders tried to navigate both public health and economic considerations. Past early April, around 8-in-x Democrats (81%) said their greater business was that land-level restrictions on public activeness would be lifted as well quickly, a view shared by only around half of Republicans (51%). That 30-point difference would grow to 40 points by early on May.

In addition to differences over government restrictions, Democrats were more than likely than Republicans to say that social distancing – or fifty-fifty personal actions more broadly – made a big difference in slowing the outbreak. Effectually 7-in-ten Democrats (69%) said in early May that social distancing measures were helping reduce the spread of the virus a lot, compared with effectually half of Republicans (49%). In mid-June, 73% of Democrats said the actions of ordinary Americans affected the spread of the virus a great deal, compared with 44% of Republicans.

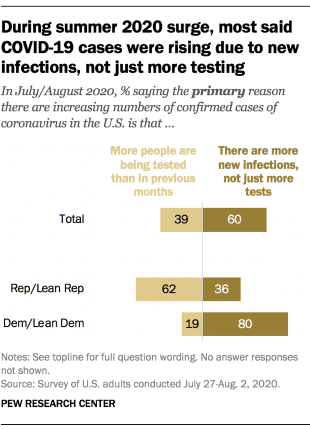

Partisans also differed over the reasons behind the ascent case counts in the summertime of 2020. Well-nigh Republicans accepted Trump'due south claim that the growing number of cases was primarily a effect of increased testing, rather than a combination of testing and a real increase in infections. Eight-in-ten Democrats pointed to more infections, not only more testing.

And then at that place was the subject of masks. While surveys consistently showed that a majority of Americans reported wearing masks in stores and other businesses, divisions past party stood out. In early on June, 76% of Democrats said they had worn a mask in stores all or virtually of the time in the by month, compared with 53% of Republicans.

Mask-wearing became more than widespread in both parties as time passed, especially as Trump donned a mask in public for the first time and the virus moved from more Democratic parts of the country to more Republican ones. But an assay of volunteered survey responses in September underscored the ongoing differences in opinion over face coverings:

"I live in Missouri in a smaller boondocks, less than 5K. Anybody thinks it's made up, no one wears masks or social distances. […] I don't feel safety or protected past my managers only I also can't say anything considering I demand the job." –Woman, 36

"I wear [a mask] for at least 8 hours a 24-hour interval forth with a confront shield, gloves and lab coat. I run across approximately 100 patients a day and when I hear people mutter about having to wearable it for 20 minutes or those who refuse to wear it, I just have to scream silently inside." –Woman, 59

"I have chronic asthma so I am fearful of being exposed to the coronavirus. It makes me extremely aroused to go out and encounter people not wearing masks or keeping social distance. And my intense dislike of Trump has grown because he lies near the coronavirus and there is blood on his hands. His lack of telling the truth about the coronavirus and his attempt to use the public health systems of the U.Southward. for his ain political ends are the equivalent of murdering thousands of people." –Man, 73

"Forced to wear masks for a virus that killed less than ten,000 people, I am more likely to be murdered in Kansas City than grab COVID at that place." –Man, 28

"The unabridged unnecessary shutdown of the country got my husband furloughed for nine weeks, more regime overreach with mask orders, people are just so terrified to live it's icky, so the ones of us like me who aren't scared get treated like we are awful people" –Woman, 31

"Being forced to wear a completely useless mask when going into businesses. I have bad allergies and can't breathe well. The CDC has reported that the masks are useless, which to me indicates they are virtue signaling items and are being used to control people." –Woman, seventy

In the bigger pic, the disputes over shutdowns, social distancing and masks pointed to partisan differences over whether the land should place greater emphasis on stopping the spread of the virus or on restarting the economy.

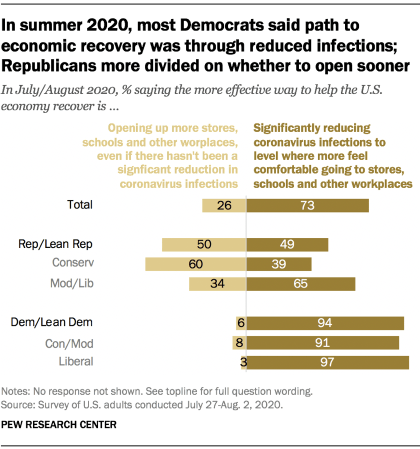

The vast majority of Democrats (94%) said in the summer that the more than effective fashion to ready the economy was to reduce infections to a level where more people would feel comfy going to stores, schools and other workplaces. Republicans were divided: Half said, for the sake of the economic system, these kinds of places should open up even without a significant reduction in infections.

Far-reaching changes to the routines of daily life

Pandemic-related closures forced Americans to make wholesale changes in their everyday lives, from the mode they attended religious services to the manner they connected with friends and family unit, attended exercise classes, shopped for groceries and much more. Many of these activities moved online – so much and then that 53% of adults said in April that the internet had been essential to them during the first weeks of the outbreak.

Even personal living arrangements changed for a sizable share of the public: In a June survey, 22% of U.S. adults said they or someone they knew had moved because of the pandemic.

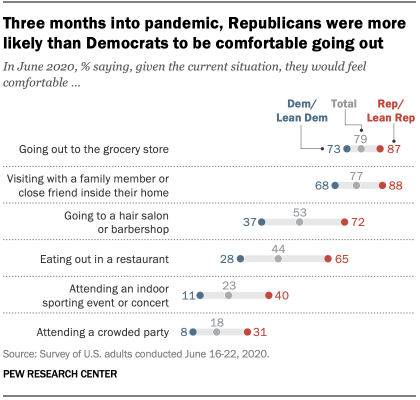

While people from all walks of life were personally afflicted, there were persistent partisan divides in Americans' comfort level with a range of daily activities. In the summer of 2020, Republicans were more probable than Democrats to say they were comfortable going out to the grocery store, visiting with family or friends inside their domicile, going to a pilus salon or barbershop, eating out in a eatery, attending an indoor sports event or concert, and attention a crowded party. On some measures, Republicans became much more comfortable as the pandemic wore on, while Democrats remained more than hesitant. In June, around two-thirds of Republicans (65%) said they would feel comfortable eating out at a eating place, up from 29% in March, fifty-fifty as Democrats remained mostly uncomfortable with the idea.

Back-to-school flavor brought more partisan divides. In tardily July, 36% of Republicans but only six% of Democrats said Chiliad-12 schools in their expanse should offer in-person classes v days a week; 41% of Democrats but simply 13% of Republicans favored online classes 5 days a week. When asked about the factors local school districts should take into consideration when deciding whether to reopen, Democrats focused more than on the possible health risks to students and teachers; Republicans focused more on the harms caused by the lack of in-person instruction, such as students falling behind and parents non being able to work with their children at habitation.

As the presidential election approached, Americans differed not only over whom they planned to vote for, but how they planned to cast their ballots. In a late summer survey, most registered voters who supported Joe Biden (58%) said they would vote past mail – taking advantage of an expansion of that option due to the pandemic – while roughly the same share of Trump supporters (sixty%) said they would vote in person on Election Day itself.

The holiday season brought further partisan divides. With health authorities cautioning against holiday travel, more than half of Americans (57%) said they had inverse their Thanksgiving plans a great deal or some due to the pandemic. But Democrats were far more likely than Republicans to say they had washed so (70% vs. 44%).

Unique challenges for Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans

The pandemic didn't simply betrayal partisan divides at almost every turn. It besides revealed stark racial and ethnic differences in health outcomes, financial duress and personal experiences with discrimination.

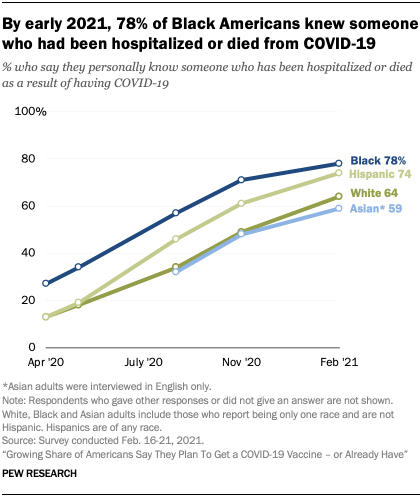

More than than half a million Americans died of COVID-19 in the first year of the outbreak alone, with the death toll sometimes exceeding four,000 people a day. But fatality rates were much higher amid Black, Hispanic and other racial and ethnic minority groups than amid White Americans. Not surprisingly, Black and Hispanic survey respondents were too consistently more likely than White adults to vocalisation health concerns over the virus and to say they personally knew someone who had suffered serious health consequences because of it.

Already in April, around a quarter of Black Americans (27%) said they knew someone who had been hospitalized or died due to COVID-19. That figure would rise to 34% by May, 57% by August, 71% by November and 78% past February 2021. By then, around three-quarters of Hispanic Americans (74%) too said they knew someone who had died or been hospitalized, fifty-fifty as White and Asian Americans remained less likely to say so.

The rapid development of new vaccines was welcome news in the fight against COVID-xix, but 1 that highlighted boosted racial and ethnic differences. In surveys in May, September, November and February 2021, a majority of Americans said they would definitely or probably get a vaccine if one were bachelor, but Black adults were consistently less likely than other adults to say this.

Besides the health disparities it exposed, the pandemic likewise led to greater fiscal hardship amongst Blackness and Hispanic adults, who were already more than likely than other Americans (on boilerplate) to take lower incomes long before the outbreak began.

Hispanic Americans were especially affected past the downturn, often because they worked in the industries hitting hardest by the recession. Just later the outbreak began in March, 49% of Hispanics – compared with 33% of Americans overall – said they or someone in their household had taken a pay cut or lost their task. By April, 61% of Hispanics – versus 43% of the overall public – said they or someone in their household had had one of these things happen to them.

Meanwhile, amid talk of the "China virus" from Trump and others, bigotry became another cause for business organization during the pandemic, specially for Asian and Blackness Americans. In June, effectually four-in-10 Asian (39%) and Black (38%) adults said people had acted as if they were uncomfortable around them because of their race or ethnicity since the outbreak began. Asian and Black adults were besides more likely to say they had been subject to slurs or jokes and to worry that someone might threaten or physically attack them because of their race or ethnicity.

A recession that hit lower-income workers hardest

The recession brought on by COVID-xix arrived with exceptional speed and severity: Unemployment rose more than chop-chop in the first three months of the pandemic than information technology did in two years of the Corking Recession.

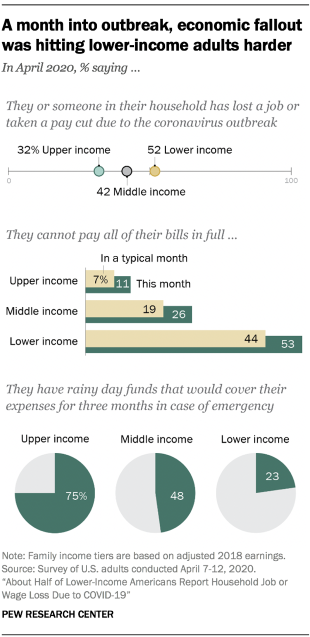

But the downturn did not affect all Americans equally. It had an especially hard touch on lower-income workers, who ofttimes worked in jobs that could not be done remotely. A Pew Inquiry Center analysis institute that 90% of the total subtract in U.S. employment between February and March of final year – 2.vi million out of ii.9 million lost jobs – arose from positions that could not exist teleworked.

By April, 52% of lower-income Americans said they or someone in their household had lost their job or taken a pay cutting, compared with 42% of middle-income adults and 32% those in the upper income tier. That translated into greater difficulties paying bills: 53% of lower-income adults said they couldn't pay some of their bills that month, far college than the proportion of middle- and upper-income Americans who said the aforementioned (26% and eleven%, respectively).

Lower-income people were also much less likely to have emergency funds gear up bated to help them withstand the recession. While three-quarters of high-income Americans and around one-half (48%) of eye-income adults said in Apr that they had rainy mean solar day funds to comprehend three months of expenses, the same was true of merely around a quarter (23%) of those in the everyman income tier.

The stimulus checks that Congress canonical in belatedly March 2020 were an important relief measure – and one of the few policy steps that drew bipartisan support – but Americans didn't utilize the coin in the same ways. A large majority (71%) of lower-income adults who said they were expecting a government payment said they would use most of the money to pay bills or for some other essential demand. Upper-income Americans were more likely to say they would put the money into savings, apply it to pay off debt or do something else with it.

Many lower-income Americans turned to other sources of fiscal aid. In an August survey, 44% said they had used money from their savings or retirement accounts to pay bills, while 35% said they had borrowed money from friends or family, 35% said they had gotten food from a nutrient bank or similar arrangement and 37% said they had received authorities food assist. Middle- and higher-income adults were far less likely to accept each of those steps.

Given these and many other challenges, it may non be a surprise that lower-income Americans were among the likeliest groups to report loftier levels of psychological distress during the pandemic.

Difficulties for young people – and parents

Another clear dividing line in the pandemic was age. A March 2020 survey institute that while older Americans worried more nearly the health effects of the virus, younger Americans expressed more than business organisation about its economic consequences, particularly since many of them were employed in service-sector jobs that were at higher run a risk from virus-related layoffs.

By early April, those risks were borne out: More than than half (54%) of Americans ages eighteen to 29 said they or someone in their household had taken a pay cut or lost their task because of the outbreak, considerably higher than the proportion of all Americans who said the aforementioned thing (43%).

For those young adults who were enrolled in college, the pandemic profoundly affected their experience. And early on evidence suggested that the financial fallout from the COVID-nineteen recession might derail some students' future plans to nourish higher: Applications for admission and financial aid in 2021 declined, particularly among economically disadvantaged youth.

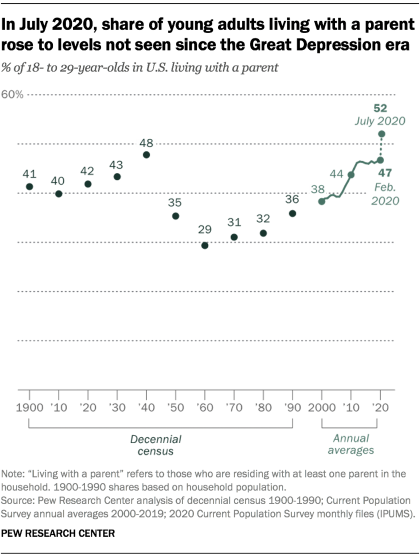

With many jobs disappearing and the college experience altered, the share of young adults who were neither employed nor enrolled in schoolhouse soared in the first few months of the pandemic. Betwixt March and June 2020, the share of sixteen- to 24-year-olds who were "disconnected" from both work and schoolhouse rose from 12% to 28%, the highest rate ever recorded for the month of June.

The difficult landscape forced many young adults to motility elsewhere. Those ages 18 to 29 were the well-nigh likely grouping to say they had permanently or temporarily moved due to the pandemic. In many cases, they went dorsum to a parent's home: Past July, a 52% majority of adults under the age of 30 were living with at least one parent, up from 47% in February and the highest pct since the Bully Depression.

While immature people faced many challenges during the pandemic, and so did parents. In April 2020, with schools effectually the land airtight, roughly two-thirds (64%) of parents with children in elementary, middle or loftier school said they were at to the lowest degree somewhat worried about their kids falling behind considering of the disruptions caused past the outbreak. Past October, even as some schools had returned to in-person learning, those concerns had not diminished. At both points in time, lower-income parents were much more worried than middle- and upper-income parents.

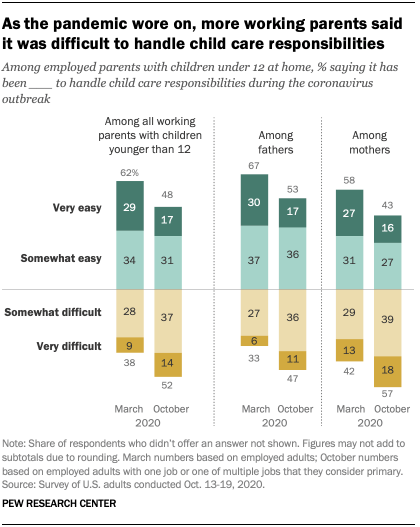

Working parents with young children at dwelling house faced detail difficulties as they tried to balance their ain job responsibilities with their children in tow.

In the early stages of the outbreak, virtually working parents with kids younger than 12 at dwelling (62%) said it was very or somewhat easy to handle child intendance responsibilities under the new circumstances. That inverse by the fall: In October, 52% of these parents said it was very or somewhat hard to handle child care. Working moms were more than likely than working dads to say it was hard to bargain with these responsibilities. They were as well more probable than working dads to face a variety of professional challenges during the outbreak, including feeling as though they couldn't requite 100% at work because they were balancing their work and parenting duties.

Unmarried moms, in particular, left the workforce in large numbers. Around two-thirds (67.iv%) of unpartnered mothers with children younger than xviii at domicile were employed and on the job in September 2020, downwardly from 76.1% a year earlier. That nine-point decrease was the biggest amid all groups of parents, partnered or not, with especially sharp declines among Black and Hispanic single moms.

A pandemic election, a change in assistants and what comes next

The coronavirus outbreak's effect on the 2020 presidential election would be hard to overstate. The pandemic changed the way tens of millions of Americans cast their ballots and almost certainly played a role in estimated turnout amid eligible voters soaring to its highest level in 120 years. Every country and the District of Columbia saw turnout ascension from 2016 levels, with many of the biggest increases occurring in places that held their elections entirely or mostly by post.

The pandemic loomed large every bit a voting consequence, too, admitting one that starkly divided supporters of the ii major candidates. In a survey a month earlier the election, 82% of Biden supporters said COVID-19 would be very important to their vote, a view shared by just 24% of Trump supporters. Later on the election, Biden supporters again overwhelmingly pointed to the outbreak – and, more specifically, Trump'southward handling of it – as a major reason for their candidate'southward victory, even as few Trump supporters agreed (86% vs. xviii%, respectively). Majorities in both camps did concur that the expanded availability of early and mail service-in voting was a major reason for the result.

When Biden took over from Trump in January, he speedily struck a different tone on COVID-19, warning that the nation's decease price would climb in the months ahead and that the situation would "go worse before it gets better." The new president's first legislative priority was to try to push a $i.9 trillion relief program through Congress in response to the ongoing public health and economic crunch. He simultaneously vowed that his administration would deliver 100 million vaccinations in its first 100 days in office.

Surveys in early 2021 showed that Americans continued to see the pandemic as a pressing issue in the months ahead. In January, around eight-in-x Americans – including majorities in both parties – said strengthening the economic system (80%) and dealing with the outbreak (78%) should exist a top policy priority for Biden and the new Congress, higher than the share who said the same most all other problems asked about in the survey. In early February, vii-in-x adults – once more including majorities of Democrats and Republicans – said reducing the spread of infectious diseases should be a top long-term foreign policy goal for the nation.

While the economy began to show some signs of recovery in early 2021, the lasting imprint of the COVID-19 recession was coming into clearer view. In Jan, about half of non-retired adults (51%) said the economic impact of the outbreak would make it harder for them to accomplish their long-term financial goals. That included 62% of those living in a household that had experienced job or wage losses during the pandemic.

There were also signs of ascent public dissatisfaction with some aspects of the nation's response to the outbreak. In mid-February, a declining share of Americans said public wellness officials and state and local elected officials were doing an first-class or good job responding to the outbreak, and around half (51%) said new variants of the coronavirus would lead to a major setback in the country'due south efforts to control the disease.

At the same time, Americans expressed optimism on other fronts, including in their views of the new administration and the growing availability of vaccines. More half the public (56%) said in mid-February that Biden's plans and policies would meliorate the nation'southward response to the virus, and around three-quarters expected the national economic system to better a lot (51%) or a little (25%) if a large bulk of Americans got the COVID-19 vaccine.

Willingness to get the vaccine was on the rising, too, including amid people who had previously expressed much more skepticism. In the mid-February survey, effectually seven-in-ten Americans (69%) said they would definitely or probably become a vaccine or that they had already gotten at to the lowest degree the offset dose. That was up from 60% who said they would definitely or probably get the vaccine in Nov 2020. A majority of Black Americans (61%) said they planned to become inoculated or had already been vaccinated, up from just 42% three months earlier.

Title photos, from left to correct: Steve Pfost/Newsday via Getty Images; James Cavallini/BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images; Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images; Alex Wong/Getty Images; Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images. Photo analogy by Pew Enquiry Center.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/2021/03/05/a-year-of-u-s-public-opinion-on-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

0 Response to "This Election Mom Knows Best Again"

Post a Comment